South America 2014

Travel, see the world, that's what I want to do! Whenever I hear or read something

about pretty much any place on Earth, I want to go there and have a look. Internet, Google Earth, Streetview, they're all great, but they can't beat being there,

speaking to the locals, getting a taste of the place. Hence the domain of this

blog: See for myself!

From May to November 2014, Eric and I are traveling around South America. We are

starting in Colombia, and gradually working our way South, hoping to get to Patagonia by the time spring arrives there.

I hope you enjoy reading about our travels. Welcome to my blog!

This blog in Dutch / lees dit in het Nederlands

2011 - 2014 California blogs (Dutch only)

We arrived in Bogotá, Colombia, on May 10th, 2014.

On May 14th we traveled to Medellín, Colombia.

On May 22nd we traveled to Taganga, Colombia.

The Caribbean Sea was shiny and flat, with tiny waves lapping softly on

the beach. Children played in the water, shouting at each other, and

their parents threw them no more than an occasional unconcerned glance.

A series of hollow pops sounded as a couple playing beach tennis hit

a long streak. The sun was already moving down toward the dusty brown

hills behind me, and the worst of the scorching midday heat was over,

but it was still uncomfortably hot. From the wooden lounge chairs

ahead of us, painted red, yellow, and blue, in the colors of the

Colombian flag, a barefoot teenager sauntered over. He asked us if we

wanted to rent two of them. I shook my head. We had already found what

we were looking for. Underneath one of the very few trees on the beach

lay a dead tree trunk, bleached white, worn smooth, and - remarkably

- not claimed by anybody. Eric whipped off his shirt and headed for

the water, while I sat down, one hand on Eric’s shirt to keep it from

blowing away in the hot, dry breeze.

Eric hadn’t even reached the waterline when I saw a man come over,

trudging through the soft sand. He sat down on the tree trunk, about

a meter and a half away from me. I glanced over and nodded politely.

He was very dark brown and had a pot belly. A rim of short grey hair

circled his bald pate, and he had a small grey moustache. He wore

white swimming trunks, and he was dripping wet. Wiping seawater off

his face, he stared at me with undisguised curiosity. Then he smiled

and asked me in Spanish where I was from.

I was tired and hot, and not in the mood for conversation, so I

pretended I didn’t understand. “No Español,” I said with an

apologetic shrug, and turned away.

“Where are you from?” he asked in crystal-clear English, albeit with

a thick accent.

I smiled but didn’t say anything.

“USA?” he asked, and I shook my head. “Germany? England? France?” I

shook my head again. “Olanda?”

I nodded ever so slightly.

“Aaaahhh, Olanda!” He grinned from ear to ear.

I couldn’t help but smile in return. “Is that good?” I asked.

“Oh, yesss! Olanda, wonderful country!” His small black eyes shone

with pleasure.

“Have you ever been there?” I strongly dislike how some people have

firm opinions of countries they have never visited, and I suspected

this might be the case here.

“Oh, yesss! I visit Olanda many times!”

“Really? How co-”

“Rotterdam, Delft, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Enschede...” He trailed off,

but before I could speak, he continued, “Venlo, Maastricht, Breda.

Where are you from?”

“Eindhoven.”

“Ah, Eindhoven! I was there. In the South.”

I turned slightly on the tree trunk, to face him. “Why were-”

“Sometimes I stayed several months,” he said, cutting me off. “I

stayed with my friend, Jan, in Dordrecht. A wonderful man. The people

from Olanda, they are so kind. From there, I visited many other

countries. Denmark, Germany, Belgium, France, Austria…” He wiped a

drop of water off his cheek.

“So how come you-”

“Italy, Spain, England, Luxemburg, Sweden… But the people of Olanda,

they are the best. My wife, I even took her with me one time, to see

for herself.”

I waited for him to continue.

“I was expert of Jim,” he said, and he leaned back and nodded

proudly.

“Jim?” I looked at him in confusion.

“Stone. Jim.” He pursed his lips and nodded again.

I gave him a blank look.

“Like jewel.”

“Gems!” I chuckled.

The man nodded curtly. “I was good at estimating the price. The

first time, I went to Antwerp, but my flight was to Amsterdam, so

first I visit Olanda. I had never been outside of Colombia before.

It was a great time.” He turned away from me and gazed out over the

smooth Caribbean Sea.

I took a swig from my water bottle and waited patiently.

Finally he turned back to me. “The people I worked with in Europe,

the Jim people, got me into the business.” He gave me a

pointed look, with one raised eyebrow, and continued. “They saw

that I was smart. I am very good at strategic thinking,” he said,

and he grinned and tapped his forehead with his index finger.

“And they knew I was safe. I could be trusted with Jim, so I could

be trusted with money. Big money.”

I looked at him, searching his face, wondering what he was

talking about.

“I was good at it,” he continued. “I became the best. I became

very rich.”

From the corner of my eye I saw Eric walking up the beach. I

cleared my throat. “I’m sorry,” I said, “but I’m not sure I

understand. How did you become rich? From selling gems?”

“No!” He laughed. “The money was from cocaine.”

I blinked rapidly. “You- you smuggled cocaine?”

“Only money.”

“To Europe?”

He laughed heartily, his paunch shaking. “To Colombia of

course!”

“So you smuggled drug money back to Colombia?” I asked

incredulously.

“Smuggling, sometimes. I already said, I am good at strategy.”

He grinned at me. “There are other ways. Better ways.”

Eric arrived at the tree trunk and grabbed his shirt, smiling

politely at the man. “Do you want to head on back to Taganga?”

he asked me in Dutch.

I replied in English, “I was just talking to this gentleman.”

Shifting over on the tree trunk to make room for Eric, I

added, “Why don’t we stay for a few more minutes?”

Eric looked curiously at me, but sat down. I introduced Eric and

myself, and the gem expert said his name was Nelson

López.

“Nelson has visited the Netherlands many times,” I said to Eric,

hoping to pull the conversation back afloat. And he’s a top dude

in international cocaine traficking and filling me in on the

details, I wanted to add, but I wasn’t sure how to work that

in. Turning back to Nelson, I said, “Are you going back to Olanda

soon?”

“Oh, no.” Nelson shook his head. “I don’t do this anymore.” He ran

his right hand down his left arm, stripping off drops of water, and

then ran his left hand down his right arm. “I was doing very well,”

he continued. “Very, very well. Making a lot of money. I could have

bought one of those.” He waved his hand casually toward the other

end of the bay, where a huge pleasure yacht lay at anchor. “I could

have bought anything I wanted to. But I stopped.”

“Why?”

“It was God.” He looked straight at me, his eyes bright, waiting

for my reaction.

“God?”

“God told me to change.”

“He spoke to you?” I asked. “Like in a vision or something?”

“Yes. I said to God, I am not a religious man, I don’t have anything

to do with the church. But God, He said, ‘I am claiming you now.’ He

showed me two rooms.” Nelson lifted his arm and sketched two

rectangles in the air. “One room was full of boxes of cash. Dollars.

It was a big room, maybe five meters by five meters, and the boxes

were up to the ceiling. It was a lot, a lot of money.” He paused

and grinned at me, his eyes sparkling.

I asked the obvious question. “What was in the other room?”

“A bible.”

“Just a bible?”

“Yes, only one bible. On the floor. The first room had billions

of dollars, the second just one book. And God made me choose.”

I nodded, prompting him to continue.

“God was giving me an important message. He was telling me that I

was living a bad life, but I could still change. He wanted me to

change, but it was my choice. So I changed. I chose the second room,

with the bible, and I stopped with the business.”

“The other people in the… business, did they let you leave? I thought

that was impossible.”

Nelson shrugged. “I made the decision to leave, so I left. Now, I

am a Pastor.”

“A Pastor!” I chuckled. “That’s quite a change! In Taganga?”

“No, in Santa Marta. Taganga is no good, too many drugs. I am

different now, I want to stay away from drugs.” Nelson frowned. “One

time, when I was a Pastor for seven years, an old friend came to

talk to me. He said, ‘Nelson, please help us one time. Just one more

time.’ But I said no.”

“What did he want you to do? Smuggle more drugs money back to

Colombia?”

That last sentence was largely for Eric’s benefit. He had been

listening to us in silence, no doubt trying to figure out what we

were talking about, and I suppressed a chuckle when I saw his eyes

widen.

“Yes. There was a lot of money in Italy. They wanted me to move it here.

I would get twenty percent of the total.” He pointed at the yacht

out in the bay. “Enough to buy that, two of them. It was tempting,

but I knew right away that it was a test from God, so it was very

easy for me to say no. And my friend, a year later he also stopped

with the business. Now he comes to my church.”

I nodded, smiling.

“Now my life is calm. I live in Santa Marta. Sometimes I come here,

for the beach. Sometimes I go to Bogotá because two of my children

live there. I have five children, fifteen grandchildren, and two

great-grandchildren.” He grinned widely. “I am a poor man, but I am

living a good life.”

“That’s great,” I said.

Suddenly Nelson got to his feet and placed his hands in his sides.

He squinted up at the sun and then turned to us. “Okay,” he said,

extending his right hand. “I am going to swim, and then I am

going back to Santa Marta.”

Eric and I also got up, and we shook hands.

“Enjoy your travels in Colombia! Bye!” Nelson turned on his heels

and headed toward the water.

We stared after him, speechless, watching as he stepped into

the tiny waves that lapped softly on the beach.

After a few days in Bogotá, we flew to Medellín, the

second largest city in Colombia, with 2.5 million inhabitants. For

backpackers who need to watch their spendings, flying may not sound

like the right way to travel. However, taking a bus from Bogotá

to Medellín costs about $50 and takes 10 hours, whereas flying

costs $60 and takes an hour and a half. We did the math.

After a few days in Bogotá, we flew to Medellín, the

second largest city in Colombia, with 2.5 million inhabitants. For

backpackers who need to watch their spendings, flying may not sound

like the right way to travel. However, taking a bus from Bogotá

to Medellín costs about $50 and takes 10 hours, whereas flying

costs $60 and takes an hour and a half. We did the math.

We came to Medellín to take a Spanish course. On Thursday and

Friday mornings, at the ungodly hour of 7:30, Eric and I sped down the

hill on foot, from our apartment to the language school. By eight

o’clock, we were both sweating away in class; it was around 32

oC during the day, the classrooms were not air-conditioned,

and the windows could not be opened because of the traffic noise.

Eric learned basic Spanish from Lorraine, and I had

conversacións with Leidy and grammar from Gloria. We were

done at noon, after which we had a simple set lunch at a nearby

restaurant and then trudged back up the hill to our apartment, to

spend the rest of the afternoon studying.

Eric learned basic Spanish from Lorraine, and I had

conversacións with Leidy and grammar from Gloria. We were

done at noon, after which we had a simple set lunch at a nearby

restaurant and then trudged back up the hill to our apartment, to

spend the rest of the afternoon studying.

On Saturday we visited the museum of Antioquia (the Colombian state of

which Medellín is the capital), and walked around the downtown

area. On Sunday we took one of the new cable-cars up into the hills.

These cable-cars are part of the metro system, and they give the

inhabitants of the poorer neighborhoods, up on the steep slopes, easy

and cheap access to the city.

We walked back down to the city through

one of those poor neighborhoods.It was fascinating to see how life

here is focused entirely on the street - everyone was outside, sitting

in doorways or on curbs, chatting to neighbors. I’m not sure that

walking here as a tourist is advisable, but we never felt

threatened.

We walked back down to the city through

one of those poor neighborhoods.It was fascinating to see how life

here is focused entirely on the street - everyone was outside, sitting

in doorways or on curbs, chatting to neighbors. I’m not sure that

walking here as a tourist is advisable, but we never felt

threatened.

From Monday through Wednesday we were back in class; Eric with

Nathalie, and I with Leidy. Our classes were now in the afternoon,

from 1 - 5 pm, which meant we spent our evenings and mornings doing

homework. The classes were fun; I learned a lot of Spanish, but I

especially enjoyed learning about Colombia and its inhabitants

through my teachers.

Central Medellín has a lot to offer, but we stayed in the hip,

up-and-coming neighborhood of El Poblado. There are plenty of

restaurants and bars here, our language school was here, and it’s

safer than the center. We rented a furnished apartment. It cost roughly

the same as a hotel room, but it was much roomier and gave us the

opportunity to prepare our own meals and do laundry.

Central Medellín has a lot to offer, but we stayed in the hip,

up-and-coming neighborhood of El Poblado. There are plenty of

restaurants and bars here, our language school was here, and it’s

safer than the center. We rented a furnished apartment. It cost roughly

the same as a hotel room, but it was much roomier and gave us the

opportunity to prepare our own meals and do laundry.

May 14: arrival in Medellín, by Avianca Airlines from

Bogotá, Colombia

May 22: departure by Avianca Airlines, to Santa Marta, Colombia

The state of Antioquia is one of Colombia’s wealthiest.

Paisas, as its inhabitants are called, are said to work

hard and to be hospitable. And they’re proud of their land.

Coffee plantations and lush forests grow side by side in the fertile

soil. “Sow pebbles there, and you’ll harvest rocks,” Andres claimed

with a proud grin. We met him in the Amazon region, where he was a

tuk-tuk driver, saving up every penny to return home. Antioquia’s

capital is Medellín, Colombia’s second city, thriving and

bustling. Tall concrete buildings line the churning Medellín

River, while low-level residential neighborhoods cover the hillsides.

Medellín, nicknamed City of Eternal Spring because of its

pleasant climate, has quite a reputation: the women in this city are

said to be the most beautiful in the world.

Medellín is also one of the best cities in northern South

America to take a Spanish course, and, with over five months in South

America ahead of us, Eric and I were in serious need of just that. As

my Spanish was better than Eric’s, they put us into two different

classes. I watched a smiling Eric follow Lorraine’s swaying hips into

a classroom, and then started my own class with Leidy. Leidy, a bright

young woman who has a university degree in Spanish literature, but

speaks virtually no English, threw me in at the deep end. After two

hours of profuse sweating (Eternal Spring must be warm) and a

conversación class on religion and poverty in Colombia

- in Spanish! - I was ready to drop.

Medellín is also one of the best cities in northern South

America to take a Spanish course, and, with over five months in South

America ahead of us, Eric and I were in serious need of just that. As

my Spanish was better than Eric’s, they put us into two different

classes. I watched a smiling Eric follow Lorraine’s swaying hips into

a classroom, and then started my own class with Leidy. Leidy, a bright

young woman who has a university degree in Spanish literature, but

speaks virtually no English, threw me in at the deep end. After two

hours of profuse sweating (Eternal Spring must be warm) and a

conversación class on religion and poverty in Colombia

- in Spanish! - I was ready to drop.

“Are you from a wealthy family?” I asked, fighting to keep my eyelids

open and my eyes focused on Leidy’s freckled face. This may sound like

a bold question, but we had been discussing the lack of opportunities

for education for the poor, and Leidy had just told me about her

university education.

Leidy picked some lint off the sleeve of her blue language school polo

shirt before she turned to me. “No, my mother’s family is poor,” she

answered, “but the government paid for my education.” Looking straight

at me without blinking, her face expressionless, she continued,

“Because my father was asesinado while working for the

government.”

That sounded an awful lot like asassinated. “Asesinado?” I repeated,

checking to see if I’d heard right.

That sounded an awful lot like asassinated. “Asesinado?” I repeated,

checking to see if I’d heard right.

Leidy nodded. She then told me that her father had been a bodyguard

to a politician. He had been good at his job, and had prevented

several attacks on the politician’s life. Criminals accosted him, and

told him to butt out. He didn’t. They threatened him, and he ignored

them. And then one day they abducted him, took him out into a field,

forced him to kneel, and shot him in the neck. They were members of

the Medellín Cartel. This was in 1992. Leidy was three years

old.

Yes, Medellín has a bit of a reputation, and in most of the

world it’s not for its beautiful women. Instead, people know the name

of this city because of the infamous Medellín drug cartel, run

by Pablo Escobar. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, Escobar and his

gang turned their hometown into the most violent city in the world.

In 1991, the homicide rate was 380 per 100,000 inhabitants, per year.

In comparison, this rate is close to 5 for the USA, and 1 for countries

in Western Europe. As there were roughly 1.6 million inhabitants in

Medellín at that time, this translates to more than 6000 murders

per year, or 17 per day. Leidy’s father was just one of depressingly

many.

Luckily, violence in Medellín has been on a steady decline in

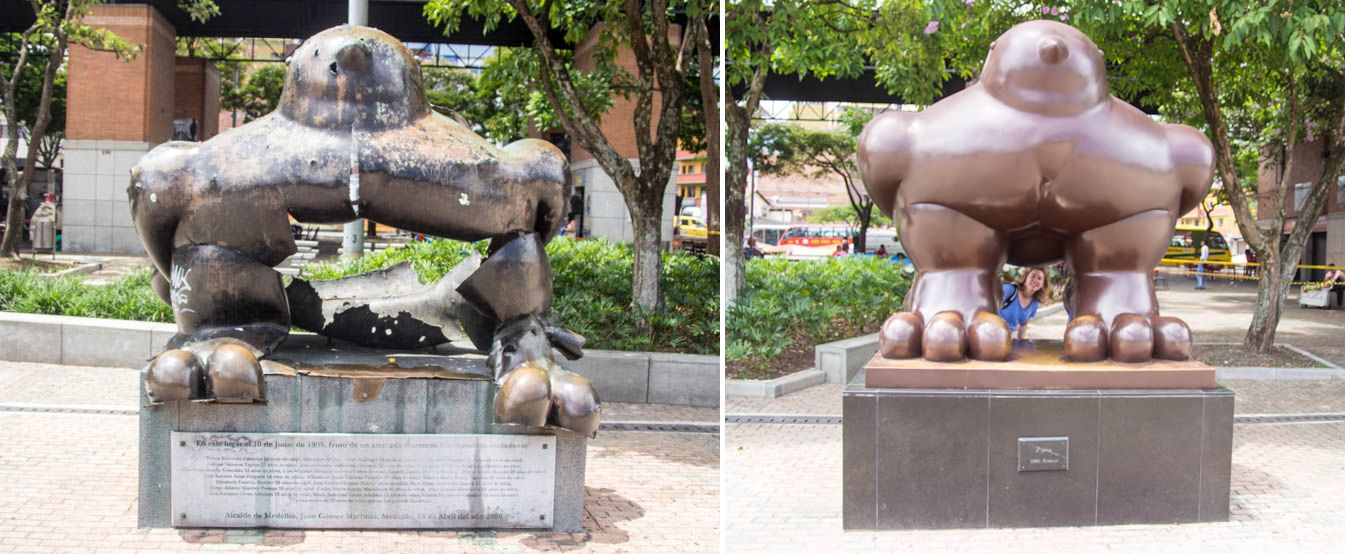

the past ten years, and the city is doing very well. After the Pajaro

de Paz (Bird of Peace) sculpture by Medellín-born Fernando

Botero was blown apart, killing twenty-three, Botero did not bow to the

criminals (read my blog on

Botero).

Instead, he insisted that the remains of the blown-up bird

be left where they are, and he placed a new bird next to it, as an

“homage to stupidity.” That reaction appears to be typical for the way

the city’s inhabitants are dealing with their bloody past: look it in

the eye, acknowledge it, and move on. The mayor has called on his

citizens to learn English, to facilitate the increasing number of

foreign visitors. Creative recycling solutions, such as the use of

discarded soda bottles to build low-income housing, have drawn

world-wide attention, and a brand-new metro system, including cable

cars that reach up into the poor neighborhoods in the hills, won the

city the title of

Most Innovative City

in 2013. When speaking with the locals, it’s hard not to become

infected with their enthusiasm, their faith in a bright future, and

their eagerness to work hard to achieve it.

Luckily, violence in Medellín has been on a steady decline in

the past ten years, and the city is doing very well. After the Pajaro

de Paz (Bird of Peace) sculpture by Medellín-born Fernando

Botero was blown apart, killing twenty-three, Botero did not bow to the

criminals (read my blog on

Botero).

Instead, he insisted that the remains of the blown-up bird

be left where they are, and he placed a new bird next to it, as an

“homage to stupidity.” That reaction appears to be typical for the way

the city’s inhabitants are dealing with their bloody past: look it in

the eye, acknowledge it, and move on. The mayor has called on his

citizens to learn English, to facilitate the increasing number of

foreign visitors. Creative recycling solutions, such as the use of

discarded soda bottles to build low-income housing, have drawn

world-wide attention, and a brand-new metro system, including cable

cars that reach up into the poor neighborhoods in the hills, won the

city the title of

Most Innovative City

in 2013. When speaking with the locals, it’s hard not to become

infected with their enthusiasm, their faith in a bright future, and

their eagerness to work hard to achieve it.

“I know who they are,” Leidy said, back in Spanish class after the

weekend. “The men who killed my father. There were two of them. I know

their names, and I know what jail they’re in.” Her brown eyes were

hard and unblinking. “There is nothing I’d rather do than murder them.

Pay somebody to kill them in jail.”

I didn’t speak.

“But you know what?” Leidy shook her head. “I’m not going to do

that.”

I nodded, encouraging her to go on.

She leaned forward and spoke intently, her eyes suddenly bright.

“What I am going to do, one of these days, is go to the jail and visit

them. At first, I won’t tell them who I am. I’ll wear my best clothes.

I’ll tell them about my university degree, and that I’m a professional

with a good job.” Leidy sat up straight and shook her head, swinging

her long hair from one shoulder to the other. She smiled. “I have a

great future ahead of me!”

“Yes, you do,” I said, and I smiled back.

She fell back in her chair, her face suddenly serious. After a pause

she said, softly, “And then I’ll drop my father’s name. I’ll tell them

who I am.”

I waited for her to continue.

Leidy frowned. “Those men, they’ve spent the past 22 years in jail and

they’re never getting out. They’re old men now. I think they

understand.”

I shook my head slowly. “Understand what?”

“That they may have killed my father, but they did not kill me. Because

of them, I had to grow up without a father, and I was very poor, but

look where I am now.” She grinned widely. “I win!”

Colombia is in mourning. It has been since April 17th.

That’s the day this country’s most famous citizen, described by the

president as “the greatest Colombian who ever lived,” passed away.

As all true book-aficionados surely know, I am referring to Nobel

Prize-winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez. His books dominate

every bookstore window, he features prominently on the country’s

primary

website,

and visitors line up in front of the Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Cultural Center in Bogotá.

Colombia is in mourning. It has been since April 17th.

That’s the day this country’s most famous citizen, described by the

president as “the greatest Colombian who ever lived,” passed away.

As all true book-aficionados surely know, I am referring to Nobel

Prize-winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez. His books dominate

every bookstore window, he features prominently on the country’s

primary

website,

and visitors line up in front of the Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Cultural Center in Bogotá.

Unfortunately, that only leaves second place for Fernando Botero,

painter and sculptor. When we were in Bogotá, we visited the

Botero Museum. I was pleasantly surprised. Botero’s paintings and

sculptures depict people, animals, and even objects, that are very

fat, and in an odd way.

I found his work to be of a cheerful nature,

without the political commentary that characterizes Garcia Marquez’

work. One of his paintings, that had me chuckling, shows an obese Mona

Lisa, and I was highly amused by his bronze sculpture of a ridiculously

fat horse.

I found his work to be of a cheerful nature,

without the political commentary that characterizes Garcia Marquez’

work. One of his paintings, that had me chuckling, shows an obese Mona

Lisa, and I was highly amused by his bronze sculpture of a ridiculously

fat horse.

“They are not fat,” Leidy said to me a few days later, in a strict

tone of voice. Eric and I were in Medellín, taking a week of

Spanish lessons, and Leidy was my teacher. A large part of my course

consisted of conversación, and I was amazed by the

variety of topics that Leidy came up with.

For the past ten minutes I

had been struggling to express my thoughts on Botero’s work in Spanish,

and I was pleased with myself for recalling the word gordo, or

fat. Apparently, the teacher was not impressed.

For the past ten minutes I

had been struggling to express my thoughts on Botero’s work in Spanish,

and I was pleased with myself for recalling the word gordo, or

fat. Apparently, the teacher was not impressed.

“It’s a baby’s perspective,” Leidy continued. She told me that when

Botero had his first child, he became fascinated with a baby’s

perspective on the world. He thought that adult brains compensate for

this, but that babies see their parents as having very wide, flat faces,

with the eyes far apart; according to Leidy, that’s what he was trying

to illustrate.

“They’re not fat,” I read in a pamphlet the next day. As Leidy had

suggested, we were visiting the Museum of Antioquia, in downtown

Medellín. Botero is originally from this city, and he donated a

large number of his works to the museum. “They’re voluminous,” the

text read, “and this makes them sensual.”

“They’re not fat,” I read in a pamphlet the next day. As Leidy had

suggested, we were visiting the Museum of Antioquia, in downtown

Medellín. Botero is originally from this city, and he donated a

large number of his works to the museum. “They’re voluminous,” the

text read, “and this makes them sensual.”

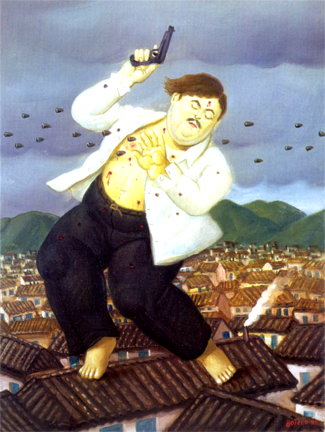

Voluminous for sure, but sensual? I still found his works mainly

cheerful, and judging from the laughter coming from the people posing

with Botero’s statues on the square in front of the museum, I was not

the only one. However, in Medellín I also discovered a more

serious note - including political commentary - in Botero’s art. For

example, it was here that we saw the famous painting “Death of Pablo

Escobar,” which depicts the head of the Medellín drug cartel

riddled with bullet holes. Hardly sensual, but certainly not amusing

either. Neither is the series of paintings on Abu Ghraib.

And then there’s the Pajaro de Paz, which shows some of the worst of

what humanity is capable of. As Eric and I stood contemplating Botero’s

statue in Parque San Antonio, I thought back to my

conversación with Leidy, the day before.

And then there’s the Pajaro de Paz, which shows some of the worst of

what humanity is capable of. As Eric and I stood contemplating Botero’s

statue in Parque San Antonio, I thought back to my

conversación with Leidy, the day before.

“Which was your favorite statue in Bogotá?” she had asked me,

and I described a small bird. A cute, fat bird.

Leidy nodded slowly. “The original statue was very large,” she said,

and her face tightened. “Go to Parque San Antonio.” Then she told me

the story of the park.

In 1994, in the midst of the drug wars, the city of Medellín

opened Parque San Antonio in one of its poorer neighborhoods, in an

attempt to improve the locals’ quality of life. To liven up the

rather sad-looking park, which was all pavement and no trees, Botero

donated a large sculpture of a fat bird, the Pajaro de Paz, or Bird

of Peace. One day in 1995, there was a musical event in the park,

and it was filled with people. Then, suddenly, the Pajaro de Paz

exploded. Explosives had been placed in its hollow belly, through

a hole at the bottom.

Shards of bronze were ripped off and flung

outward. It was a massacre. Twenty-three innocent people died, the

youngest of whom was a 7-year old child, and many others were

injured. It was probably a FARC bomb; the FARC, although it claims

to be a political party, has close ties with the cocaine industry,

as drug running is one of its major sources of income. They were

probably hurt by the governmental crack-down on drugs in the early

1990’s, and the bomb may have been a form of retaliation.

Shards of bronze were ripped off and flung

outward. It was a massacre. Twenty-three innocent people died, the

youngest of whom was a 7-year old child, and many others were

injured. It was probably a FARC bomb; the FARC, although it claims

to be a political party, has close ties with the cocaine industry,

as drug running is one of its major sources of income. They were

probably hurt by the governmental crack-down on drugs in the early

1990’s, and the bomb may have been a form of retaliation.

In 2000, the city wanted to remove the remnants of the exploded

bird from Parque San Antonio. Botero protested loudly. He requested

that the destroyed Pajaro de Paz be left where it was, as a

memorial to the massacre, and as an “homage to stupidity.” He then

made a copy of the original statue, and had it placed next to the

destroyed one. The destroyed and the new Birds of Peace still

stand next to each other today.

I know diddly squat about art, but the blown-up Pajaro, the

sculpture of a bird that became a weapon of mass destruction,

truly touched me. And Botero’s reaction to this horrific abuse

of his work of art gives me hope for the future of humanity. The

president may believe that Garcia Marquez is the greatest Colombian

who ever lived, but my vote goes to Botero.

I know diddly squat about art, but the blown-up Pajaro, the

sculpture of a bird that became a weapon of mass destruction,

truly touched me. And Botero’s reaction to this horrific abuse

of his work of art gives me hope for the future of humanity. The

president may believe that Garcia Marquez is the greatest Colombian

who ever lived, but my vote goes to Botero.

Our very first stop on our five-plus month journey around South America

was Bogotá. We spent three days here, to visit the city and plan

our next steps.

Bogotá has a beautiful colonial city center, and we spent several

hours admiring Plaza De Bolívar and walking the nearby cobblestone

streets. We found out how to score a cheap ($2 - $3), yet good, lunch:

simply pick a restaurant that serves only a set lunch and that has

plenty of customers, and have whatever they’re serving (usually rice,

bean soup, chicken, and a bit of salad).

Bogotá has a beautiful colonial city center, and we spent several

hours admiring Plaza De Bolívar and walking the nearby cobblestone

streets. We found out how to score a cheap ($2 - $3), yet good, lunch:

simply pick a restaurant that serves only a set lunch and that has

plenty of customers, and have whatever they’re serving (usually rice,

bean soup, chicken, and a bit of salad).

The city center has several museums, most of which we visited. One of

our favorites was Museo Botero, with a large collection of paintings

and sculptures by the Colombian artist Fernando Botero. We had never

heard of him before, but found his works - especially the oddly fat

people and animals - refreshing, unusual, and amusing.

The city center has several museums, most of which we visited. One of

our favorites was Museo Botero, with a large collection of paintings

and sculptures by the Colombian artist Fernando Botero. We had never

heard of him before, but found his works - especially the oddly fat

people and animals - refreshing, unusual, and amusing.

The indigenous peoples that lived here before the Spaniards came were

experts at working with gold. The Spaniards stole as much of this

gold as they could find, and shipped it to Spain. However, any golden

artworks that the Spaniards did not get their hands on are now on

display at the Museo Del Oro. Beautiful decorative pieces and

religious objects give a slight peek into what these peoples’ lives

may have been like, and make this into Colombia’s primary museum.

The indigenous peoples that lived here before the Spaniards came were

experts at working with gold. The Spaniards stole as much of this

gold as they could find, and shipped it to Spain. However, any golden

artworks that the Spaniards did not get their hands on are now on

display at the Museo Del Oro. Beautiful decorative pieces and

religious objects give a slight peek into what these peoples’ lives

may have been like, and make this into Colombia’s primary museum.

Bogotá is also Colombia’s capital city, and this is where the

country’s elite work and play. We visited the wealthy Zona Rosa

neighborhood, where Dolce & Gabbana and Swarovski cater to the rich

and famous, and beer is sold at European prices.

May 10: arrival in Bogotá, on an Air France jet from Paris, France.

May 14: departure by Avianca Airlines to Medellín, Colombia.

“I’ll wait for you right here!”

“Okay, be right back.” I nodded at Eric and headed over to the other side

of the lobby. My spirits were high. For the past hour we had walked the

cobblestone streets of the colonial center of Bogotá, and now we

were at the Botero Museum. I was eager to learn more about Colombian

culture. All I needed was a quick pit stop before immersing myself in the

works of one of this country’s most famous artists, sculptor and

painter Fernando Botero.

I opened the door to the women’s bathroom and stopped smack on the

threshold. A crowd of young schoolgirls filled the entire area between the

stalls and the sinks. Doors slammed open and shut, the paper towel dispensers

clattered loudly, and laughter echoed off the tiled walls. I hesitated,

tempted to backtrack and wait outside, when one of the girls looked over

and saw me. She nudged her friends, and a wave rippled through the room.

Within seconds, the entire group fell silent and twenty girls in white

uniform shirts and dark green skirts stood staring up at me, their eyes

wide. Then one of the smaller girls lifted her hand and gave a tiny, shy

wave. Touched by the gesture, I smiled and waved back, and the spell was

broken. The girls laughed cheerfully, faucets spewed water and white noise,

and some of the girls started to push by me on their way out.

A few minutes later I walked out of the empty bathroom, shaking droplets of

water off my hands. I entered the lobby and stopped dead once more. Eric

stood with his back against a wall, a throng of perhaps thirty schoolchildren

crowding around him in a semi-circle. He looked over at me, an amused look

on his face, and a burst of laughter escaped from my mouth. The boys and girls

in uniform turned around, saw me, and separated slightly so I could walk over

to Eric; the narrow aisle closed behind me as the children drew back in. Some

of the older ones had been bombarding Eric with questions, and now I also became

part of their game. They wanted to know where we were from, whether it was cold

there, what language we spoke. What kind of work we did and whether we had a

car. With the World Cup a few weeks away, most conversations in South America

tend to head toward soccer, and it didn’t take long for the children to bring it

up. They all knew that “Holanda” is one of the participants, and they asked us

whether we thought the Netherlands might win. Naturally, we insisted that

Colombia is going to be champion. The entire conversation was in Spanish. One

of the older boys had an iPad, and whenever the conversation stranded on a word

we didn’t understand, he looked it up on Google Translate and proudly showed

it to us.

All this time, the children’s teacher stood toward the back of the lobby,

halfway up a staircase. When I joined Eric, he placed his hands on the banister

and watched, chuckling softly. However, after the children had been firing

questions at us for about ten minutes, he called out something in Spanish.

The children at the rear of the crowd turned toward the staircase, but some of

those nearest to us whipped out cell phones and started to take photos of us.

One of the girls handed her cell phone to a friend and then boldly posed next to

us while her friend took a picture. I’m sure anyone can guess what happened next:

we got to pose with another twenty girls and boys, one by one or in pairs, as

their friends took pictures, loud laughter ringing out in the lobby.

Finally the teacher started to climb the second half of the staircase, and he

called the children over. Waving cheerfully at us, all of them speaking

simultaneously in Spanish, the children retreated to the staircase and followed

him to the second floor. Eric and I grinned widely at each other. We had, after

all, come to the museum for some Colombian culture.

Bogotá is a huge city, with 7 million inhabitants living along

a 40-kilometer north-south sprawl. Getting around the city in a car

is trying, to say the least. The lines on the pavement are no more

than rough guidelines, and size determines right of way. The major

roads in the city are an endless, black smoke-belching traffic

stand-still, and the smaller streets are a craze of pedestrians

dodging tiny yellow cabs that come screeching around corners.

Luckily, there is an alternative: the TransMilenio bus system.

On our second morning in Colombia, Eric and I walked cheerfully to

the nearest TransMilenio bus station. Eric asked for two tickets to

the center of Bogotá and the cashier passed him a single

plastic card.

“Dos,” Eric said, and he held up two fingers.

The cashier chattered in rapid Spanish, which we did not understand.

“Dos,” Eric repeated, unsure of what to do.

The cashier muttered something and waved us off, turning to next

customer. Huh. We stepped aside and were wondering what to do when

the woman who had been in line behind us came over. She said

something in which I recognized the word ajuda, or help, and

gave us a friendly smile. She appeared to be about fifty, and wore

beige pants and an old-fashioned pink sweater. Her hair, bleached

blonde, fell down to her shoulders. She held out her own plastic

card and started to make a series of movements with it. Speaking

rapidly, she repeated the motions a few more times, then asked us

whether we understood.

Eric and I looked at each other and shook our heads. “No

comprendo,” I mumbled, and Eric held up our card and threw in

another “dos” for good measure.

Looking resigned, the woman nodded and gestured for us to follow her.

We walked to the curb of Avenida Caracas and waited for the

pedestrian light to turn green. The bus platform sits at the center

of this eight-lane traffic aorta. Cars use the two outer lanes, on

both sides; the four inner lanes are for the TransMilenio buses, with

two lanes in each direction. The long, tiled platform is raised one

meter above street level, and encased in glass. We watched some buses

blow by the station at high speed in the outer bus lanes, while others

slowed down in the inner lanes. These pulled over at designated spots

along the platform, after which sliding glass doors opened, allowing

passengers to get on and off.

A row of turnstiles blocked our entry to the platform. Ducking in

front of Eric, the woman pointed at his card and then slapped a

sensor pad with her hand. Eric held his card over the sensor, a light

turned green, and he pushed forward. Reaching back over the turnstile,

he gave me the card. However, nothing happened when I held it over

the sensor. “No,” the woman said, followed by a lot of Spanish, and

she pointed at a slot in the front of the turnstile. I pushed the card

into the slot and - bingo! - the light turned green again. I gave the

woman a grateful smile. We would never have figured that out

on our own.

Our new friend asked us where we were going, and we named a station in

downtown Bogotá, close to where the museums are. She jogged

over to a large board that showed about thirty bus lines, jabbed her

finger at one, glanced around, and strode rapidly over to a pair of

glass doors where a bus was just pulling up. We followed her. The

platform doors slid open and the woman pushed her way in, fighting

the flow of passengers trying to get off, gesturing urgently for us

to stay with her. Gasping, I clutched the greasy metal bar over my

head as the bus pulled away from the platform in a violent jerk, and

I strained not to fall as the bus swung to the right. My elbow and

Eric’s backpack grazed a few faces and I mumbled apologies at the

people around us, all of whom were at least a head shorter than me.

Their friendly nods and smiles assured me that there were no hard

feelings.

Our new friend asked us where we were going, and we named a station in

downtown Bogotá, close to where the museums are. She jogged

over to a large board that showed about thirty bus lines, jabbed her

finger at one, glanced around, and strode rapidly over to a pair of

glass doors where a bus was just pulling up. We followed her. The

platform doors slid open and the woman pushed her way in, fighting

the flow of passengers trying to get off, gesturing urgently for us

to stay with her. Gasping, I clutched the greasy metal bar over my

head as the bus pulled away from the platform in a violent jerk, and

I strained not to fall as the bus swung to the right. My elbow and

Eric’s backpack grazed a few faces and I mumbled apologies at the

people around us, all of whom were at least a head shorter than me.

Their friendly nods and smiles assured me that there were no hard

feelings.

The bus settled into a constant speed and I turned to our friend,

thanking her profusely for her help.

“Are you also going downtown?” I asked.

She shook her head and explained that she was on her way to the

airport to deliver a package, and she’d be getting off the bus at

an earlier stop. She worked for Cisco as an engineer. We started a

halting conversation, limited only by my Spanish. On closer

inspection, the woman appeared to be around forty; her austere

clothing and old-fashioned glasses had made her seem older.

“Don’t trust anyone,” she muttered, glancing around. “Colombia is a

beautiful country, but the people…” She shook her head, frowning.

I raised one eyebrow, ready to defend a country I had yet to get to

know. “From what I heard, Colombians are very nice,” I said.

“Sure. Most are. But there are always opportunists.”

“There are opportunists in every country,” I countered.

“Isn’t that the truth,” she said, and sighed. “So don’t trust

anyone.”

Obviously the irony in what she said, after having approached us on

the street, was lost on her. We spoke about the museums in

Bogotá, and when her bus stop approached she admonished me

once more not to trust anyone.

“Where is your passport?” she asked.

“In the hotel, in a safe,” I answered.

“Good.” She nodded approvingly. “Don’t take a camera with you,

either.” She whipped out her cell phone and started to type a text

message. Frowning at her phone, she mumbled, “Don’t even take a

cell phone. It’ll get stolen.” The doors of the bus opened, and

she looked over her shoulder, directly at me. “God bless you,” she

said in English. Then she looked intently at Eric. “God bless

you,” she repeated. She gave a quick wave and hopped off the bus.

The bus pulled away from the platform with a roar. Even though we

clung to the overhead bars, we were flung hard into our neighbors,

yet the only looks we received were of friendly, open curiosity.

I’m sure there are opportunists in Colombia, as well as everywhere

else. But as long as there are guardian angels out there like our

personal TransMilenio guide, I’m sure we’ll be fine.

Colombia. That country somewhere in South America. Their most popular

export product is coffee… or is it cocaine? In the press, Colombia has

been largely defined by druglords, cocaine cartels, and cocaine wars.

And then there’s the guerrillas whose disruptive actions have been

tearing up the country for decades, the FARC proudly in the lead. For

as long as I can remember, the Netherlands’ ministry of foreign affairs

has been telling Dutch citizens to give Colombia a wide berth, to keep

from getting kidnapped by the FARC or caught in the crossfire of a

cartel shootout, or from simply disappearing in the jungle. Gotta go

see that place, right? Let’s go to Colombia?

Colombia. That country somewhere in South America. Their most popular

export product is coffee… or is it cocaine? In the press, Colombia has

been largely defined by druglords, cocaine cartels, and cocaine wars.

And then there’s the guerrillas whose disruptive actions have been

tearing up the country for decades, the FARC proudly in the lead. For

as long as I can remember, the Netherlands’ ministry of foreign affairs

has been telling Dutch citizens to give Colombia a wide berth, to keep

from getting kidnapped by the FARC or caught in the crossfire of a

cartel shootout, or from simply disappearing in the jungle. Gotta go

see that place, right? Let’s go to Colombia?

My interest in Colombia was first aroused in 2009, when I spoke to

several people who were on multi-month journeys in South America.

They were all insanely positive about Colombia, the new cool, up and

coming. A new president had doubled the police and military forces,

and several major drug lords had been chased down and shot. Cuba and

Russia had dropped the FARC as their BFF, and the FARC, without the

cash to buy arms, was retreating into the most distant reaches of the

jungle. Colombia was finally becoming relatively safe, and the first

Western visitors were starting to drop in. Apparently the Colombians

welcomed tourists with open arms. Go there, was the buzz among

seasoned travelers. Go there now, while the country is still pure,

while they still love us. Go there before Starbucks and McDonalds

take over the colonial town centers, before tourists become walking

wallets, before resentment sets in.

We didn’t act on our fellow travelers’ advice. A three-year stay in

California got in the way of adventurous international travel, and

Colombia was moved to the back burner. A few months ago, when Eric

and I started to make plans for a 6-month stay in South America,

Colombia didn’t even figure in. It’s too hot, we reasoned, and there’s

not a lot to see or do. Shrug. So many countries to visit, we can’t go

everywhere, right? Our friends Yvonne and Robert changed our minds.

They travelled around South America a few years ago, and in various

conversations we had on the topic they kept talking about Colombia.

It’s the pura vida, Robert said, smiling widely. And just like

that we got curious and decided we wanted to go have a look.

We didn’t act on our fellow travelers’ advice. A three-year stay in

California got in the way of adventurous international travel, and

Colombia was moved to the back burner. A few months ago, when Eric

and I started to make plans for a 6-month stay in South America,

Colombia didn’t even figure in. It’s too hot, we reasoned, and there’s

not a lot to see or do. Shrug. So many countries to visit, we can’t go

everywhere, right? Our friends Yvonne and Robert changed our minds.

They travelled around South America a few years ago, and in various

conversations we had on the topic they kept talking about Colombia.

It’s the pura vida, Robert said, smiling widely. And just like

that we got curious and decided we wanted to go have a look.

Now, several weeks later, our plane descends toward the Colombian

capital of Bogotá, and I gaze out of the window at grey

nothingness. Images of California and the Netherlands dance tirelessly

across the thick cloud cover. We moved away from California, spent

one week in the Netherlands, and are now starting a

five-and-a-half-month trip around South America; I can barely wrap

my head around all of this. We’ve got over five months of backpacking

ahead of us, in which we’ll be living out of the 25 kilograms of luggage

that we have between the two of us. Five months without a familiar face,

with strange food and foreign languages.

Suddenly the plane dips below the clouds, and a mountainous landscape

in a million shades of green dispels my troubled thoughts. Steep

forested peaks surround a fertile valley of fields and greenhouses,

and a sprawling city glimmers in the distance. Colombia. Let’s go

check it out!

Suddenly the plane dips below the clouds, and a mountainous landscape

in a million shades of green dispels my troubled thoughts. Steep

forested peaks surround a fertile valley of fields and greenhouses,

and a sprawling city glimmers in the distance. Colombia. Let’s go

check it out!